A certain generation of cricket fan will remember the days of the World Series.

The very best players, with more money, more flashy TV rights – ‘pyjama cricket’. A reverberating shock amongst cricket traditionalists.

A younger generation will remember the European Super League debacle.

The very best players, with more money, more flashy TV rights – ‘Fortnite football’. A reverberating shock amongst football traditionalists.

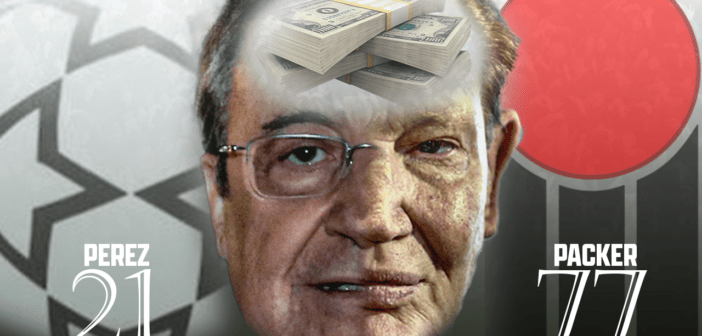

Behind the schemes are two extremely clever, power and profit-hungry businessmen. Both have had lasting impacts on the sport they involved themselves in without kicking or hitting a ball.

So how, 44 years on from the World Series formation, can we draw comparisons with the recent European Super League scandal? Can football learn from the mistakes that cricket made?

The World Series story

Kerry Packer – an Australian marketing mogul with a vision to transform cricket to a profit machine – a product.

The Australian television industry was at a crossroads. Having relied on imported USA programmes instead of commissioning self-made shows, there was a clamour for more with a “TV: Make it Australian” campaign in 1970.

Kerry’s father, Sir Frank Packer, was the controller of Channel Nine and the Associated Press Network in Australia – a huge name. He sold his Daily Telegraph flagship to a more familiar name in this country, Rupert Murdoch, in 1972.

He died in 1974, giving Kerry full control of the networks and a leverage to fulfil his vision. He wanted more Australian made programmes on the network – luckily for him, sport was included.

His forward-thinking, ruthless strategy began well – securing the Australian Open golf tournament in 1976, but cricket was a more difficult nut to crack.

The Australian Cricket Board were loyal to the ABC network – one which Packer called ‘an old-boys connection’ – as they’d broadcast it for the two decades previous.

He offered an extremely large sum to the ACB the year afterwards – 86% more than ABC – for England’s tour of Australia in 1977. It fleshed into a full series between Australia and the rest of the world. To describe it to a younger audience, it was like a deluxe, competitive version of Soccer Aid.

Gregg Chappell and Tony Greig signed on for the project – and even acted as agents to secure other players for Packer’s profit machine. However, the official cricket boards did not simply lie down to allow the change.

The two parties met in the summer to reach some form of compromise, with negotiation close to completion before Packer demanded TV rights exclusively for the 1978/79 Australia test matches. The ICC didn’t have that power, and he stormed out of the meeting.

“Had I got those TV rights I was prepared to withdraw from the scene and leave the running of cricket to the board. I will take no steps now to help anyone. It’s every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost.”

A court case started two months later, with the following needing settling after seven weeks:

- Are the contracts between WSC and its players void?

- Has WSC established that, as at 3 August, and subject to any statutory immunity conferred by the 1974 Act, it was a good cause of action in tort against the ICC based on inducement of breach of contract?

- Has WSC established that as at 3 August and subject as aforesaid, it had a good cause of action in tort against the TCCB based on the same grounds?

- Subject to the provisions of the 1974 Act, are the new ICC rules void as being in restraint of trade?

- Subject to aforesaid, are the proposed new TCCB rules void as being in restraint of trade?

- Is the ICC an employers’ association within the 1974 Act?

- Is the TCCB an employers’ association?

- If either the ICC or TCCB or both be employers’ associations, does this itself bar any cause of action that would otherwise exist?

- In the light of the answers, what relief (if any) should be given to (a) the individual plaintiffs and (b) WSC?

Justice Sir Christopher Slade sided largely in Packer’s favour, with the players not blamed for secrecy, and the ICC stretching the concept of ‘loyalty’ too far.

The small wins for the ICC only really lied in naming rights. Packer was unable to use the terms ‘Test Match’ and ‘Australia’. He couldn’t use the official cricket rules either.

The financial blows to authorities was enormous however – they had to pay court costs, with the official WSC beginning in the next Australian summer.

Throughout the next two summers, the success of WSC undulated. Overall, Packer hired 70 players for 16 “Supertests” and 38 one-day games over two seasons.

Despite it’s demise in 1979/80, the lasting effects on the sport have left Packer described as the most influential figure in modern cricket.

The Super League story

Ah, the all too familiar Super League. Nothing has been on the tongues of football fans more this month than the concoction of monetary gain emanating from Florentino Perez’s money-making scheme.

Perez himself, dissimilar to Packer, had an already powerful stronghold over football when attempting to breakaway from the leading organisation. Having served in his second term as president at Real Madrid since 2009.

“(his influence is) Gargantuan, simply put – the second greatest figure in the clubs history behind Santiago Bernabéu.

“It’s because of Pérez that Real are the juggernaut that they are right now.”

Hasan Karim, Real Madrid fan

Commercially, Perez turned Real Madrid into a global force. Having always been a big club, the ‘Galactico’ strategy could almost be likened to a one-club version of the Super League. The very best players, all in the same team.

In 2018, Germany’s Der Spiegel reported on a European Super League after uncovering documents from Football Leaks outlining the competition. The idea was for the top European football clubs to break away from UEFA and start their own competition in 2021. They did.

Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur; Italian clubs Inter Milan, Juventus and A.C. Milan; and Spanish clubs Atlético Madrid, Barcelona and Real Madrid were all invited and broke away from their respective organisations on the Monday.

The proposed competition ensured the financial safety of these elite clubs, backing them with €350 million in participation fees each season.

A factor Perez and the other owners didn’t consider was fan power. The vast majority were disgusted by the corporate greed shown by the people involved in the breakaway, including the players.

The current broadcasters and organisations also stood firmly against the ESL, with Sky in particular giving Gary Neville significant air time on the situation. Almost identical to the WSC debacle, the broadcast rights were likely in the hands of another network. Would the outrage have been the same if Sky had secured the rights?

UEFA and president Alexandr Ceferin were also playing the victim card, like the ICC. Loyalty as a concept is not owed to them, much as what Justice Slade said to the leading cricket organisation.

Unlike the WSC though, Perez’s plan did not come to fruition. Packer got two years, he lasted two days.

The Legacies

The feeling amongst fans is that the ugly head of the European Super League will rear once more – but positives have given the cloud a welcome silver lining.

Fans have already had their say – the Manchester United fans, however out of order the minority were, sent a clear message that they are fed up with their ownership. Liverpool fan-group Spirit of Shankly have met with the owners to discuss legislations that will not allow such action to go ahead again without the representation of fans’ opinion.

But to look at positives from the monetisation in the long-run, you only have to look at the WSC. Descendants include the regular establishment of One Day cricket, T20 cricket, the IPL, the Big Bash, and now The Hundred. There’s even T10 cricket in Abu Dhabi.

‘Pyjama cricket’. Coloured kits are a staple of the modern game, but from that have come sponsors galore. Especially in the aforementioned IPL, they sponsor actions alongside the physical kits. PAYtm even sponsor the umpires.

It has seen an increase in the wider audience of the game, which cricket needed as a repetitive, traditionalist sport at it’s core. Football is the world’s game, and it clearly doesn’t need this level of commercialisation to stay afloat.

Structural re-organisation and a reunion of trust between all governing bodies, clubs and fans needs to be prioritised. But as the World Series shows, distinct positivity can be extracted from a negative situation.

Football will learn that.

Follow us on Twitter @ProstInt

![Prost International [PINT]](https://prostinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/PINTtFontLogoRoboto1536x78.jpg)