Southampton’s approach to set pieces is emblematic of their attitude to football.

It can be enchantingly risqué, mostly fearless and occasionally, head scratching. It nearly always treads along the precipice between genius and madness.

On the whole, Hasenhuttl has demonstrated a conducive method to the perceived madness. Aside from poor organisation at the weekend, where Lewis Dunk went without challenge for Brighton’s first goal, data underlines how frugal Saints have proven to be when defending dead ball situations.

In the 29 games played, Southampton have conceded just four goals from set pieces. Only Fulham, Arsenal and Manchester City have yielded fewer.

They’ve also have had similar success at the other end of the pitch. Along with Manchester City, the 11 goals scored is the third highest in the league, with West Ham and Everton the two sides more productive.

Despite both facets of their game functioning relatively well, they share distinct differences in how they are approached. While their attitude to defending is one that’s founded upon a collective operation rather than personal responsibility to make a system work, offensive free-kicks and corners are the polar opposite.

Instead of a holistic structure to garner success, akin to when defending, Ralph Hasenhuttl’s attacking set piece playbook relies heavily on particular individuals to fashion and take chances.

It is understood Dave Watson, the first team assistant coach, is tasked with designing choreographed routines from dead ball situations. And though there are some cases that show there are occasional nuances to deliveries – take Stuart Armstrong’s goal against Arsenal – most of the time, each delivery has certain recurring patterns, depending on the set piece’s location.

Step 1: Defending deep set pieces

But first, let’s wet our fingers and brush through the first page of the Hasenhuttl playbook with Southampton’s rather striking modus operandi to defending deep set pieces.

In the hushed din of a COVID-19 football match, shouts from certain players are only amplified. Saints’ captain James Ward-Prowse, is usually stationed towards the front of the very high line (more on that later) due to the midfielder having the clearest sight to measure the path and trajectory of the incoming cross. He can then relay that information to subsequent team-mates.

Ward-Prowse’s role at the front of the pack necessitates him to keep the rest of those in red and white as high as possible and in a correlating, undeviating line. Here against Chelsea, Ward-Prowse can be heard shouting “right foot on line, boys!” The side-on positioning of the seven players behind him remains unmoved throughout the whole sequence, one of the more zany ploys in the Hasenhuttl manual.

With teams recognising Saints’ lack of movement, there have been various plans in how best exploit the perceived weakness. In the case below, Chelsea elected to overload the back post and start a yard in front of Southampton’s defenders. This is to ensure they time their runs as smoothly as possible without faltering in an offside position.

As you can see, the high line leaves oceans of space between the outfield players and goalkeeper. While multiple teams on the continent initially created and thereby adopt this method, not many stay as stoically high as Hasenhuttl’s men.

As stated, it is not uncommon for teams to take up brave starting positions. But when they do, there is usually an emphasis on using the first step of the free-kick taker’s run-up as a trigger to begin dropping.

But with Southampton, as this sequence against West Brom illustrates, they often stand stationary and extremely high – look how they are positioned on the edge of the d, rather than the edge of the box.

This not only shows their methodology is an exception rather than the rule, but fights against all natural instincts. As a youngster, you are habitually told to stay ball and goal side. But with Hasenhuttl, he prefers opposition players to run off his defenders, relying on VAR and the linesman flag to call offside.

Ultimately, this is why opposing teams frequently enjoy the freedom of the box to finish a move off. Rather than call it poor undisciplined marking, there is clear method to the discernible insanity. In the first 23 games of this season, Southampton had provoked the fourth most offsides in the league (51). This statistic alone shows the collective approach to condense space is working efficiently.

Like all decisions taken in football or within all systems created, it does possess flaws and marked drawbacks. The precarious strategy can result in runs from deep (note Kyle Bartley’s in the example below) or third man movements being less likely to be caught offside. The more ground an opposition player has to cover, the more time they have to stay onside. In this instance, Bartley was onside but misses the target.

Step 2: Defending wide set pieces

Wide set pieces are instantly met with a staunch resistance to drop into their box. Southampton deem the white paint of an 18 yard-box as some sort of resistance and if they ever so slightly creep past that line, it can have dangerous ramifications.

In the below example, taken from the game against Manchester City in December, look at the stark difference in both team’s body shapes. Again, observe how Ward-Prowse is the first in line (Moussa Djenepo acts as a second wall). While Saints’ body weight is shifted onto their back leg, this presents a perfect example in how they use the 18-yard-box as a positional yardstick.

Circled in blue, Ruben Dias is already offside before the ball is even kicked.

Since the Man City game and throughout the season, Southampton’s confidence in their high positioning has continued to defy traditional footballing logic and has, in fact, got even higher. Invariably, they still use the 18-yard-box as their barometer, despite free-kicks being noticeably closer in proximity.

The fine line which Southampton continually straddle was typified against Everton, when they chose to remain acutely high, in spite of how close Lucas Digne’s deliveries were. In this instance, Richarlison is offside but forces a good save from Forster. Like Chelsea, Carlo Ancelotti regularly attempted to overload the back post with his tallest players.

Step 3: Defending corners

A flux of injuries over the winter has meant identifying recurring patterns within the set up of a defensive corner proves somewhat difficult. Various changes in personnel has led to specialist positions having a slew of players fill them.

However, the picture does become less opaque when Jannik Vestergaard is playing. The central defender tends to mark the space in the middle of the six-yard box as opposed to a player. His partner Jan Bednarek takes up a vantage point behind him and in line with the back post. Che Adams, meanwhile, routinely takes care of any ongoings encompassing the far post.

In most instances, Hasenhuttl opts for a hybrid system of man and zonal marking for the rest of the team. Though fans often detect and fret about height differences, smaller players are there to act as blockers rather than actual man-markers. In essence, their job is to be a nuisance and offer some form of resistance.

Step 4: Attacking corners

Now let this writer pretend we’ve strolled 100 yards up the other end. Regrettably, Southampton are regular consumers of profligate finishing from open-play, causing dead ball situations to only grow in importance.

Against teams that defend in a zonal system, players in the box can be separated into two groups – blockers and runners. On this occasion, Theo Walcott (A) and Adams (B) are the blockers, tasked with disrupting the blue shirts – the taller Brighton players. These are the players which are stationed outside on the edge of the six yard-box and intending to attack the initial header.

The other four all start their runs on the edge of the 18-yard-box before scurrying in different paths. Bednarek surges to the front post, Oriol Romeu and Vestergaard take middle and Ryan Bertrand sneaks round the back, hoping to mop up any flick-ons.

At the top of the piece, Prost International opined how attacking set-pieces have an individualistic feel to them. Plainly, Southampton’s process entails using Vestergaard as their standalone lighthouse that the rest gravitates towards. Ward-Prowse, almost inevitably and endlessly, aims for the head of Vestergaard, using his 6ft 7′ presence to far greater effect than last season. The other runs, while they carry intent, are mere decoys.

In the second phase of the corner below, Adams’ block on Lewis Dunk disrupts the centre-back’s momentum as he contests for a ball with Vestergaard. Dunk’s hesitation now means the Dane is able to see the ball from Ward-Prowse’s boot all the way onto his head and into the net.

Note how Vestergaard’s physical presence attracts all the blue shirts, leaving Bertrand spare at the back post.

Step 5: Attacking free-kicks

It is fair to say the final throes of the Hasenhuttl playbook do grow in simplicity. It’s not exactly the most arduous task to nitpick the exact nuances. Instead, they tend to stare right in your face, point blank in blatancy.

It goes something like this: Ward-Prowse | Vestergaard’s head | goal.

The other Southampton players are consigned to a background role, tasked with offering their best pretence in hope it throws opposing players off the scent and leaves enough space for Vestergaard to remove the ball’s leather as it flies into the back of the net.

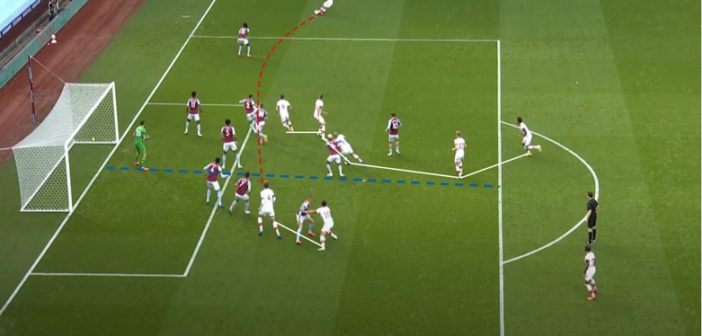

The centre-back’s second goal of the season against Aston Villa exemplifies this rudimentary yet effective tactic. Saints four players (five if you count a hovering Armstrong) are the closest side of the penalty spot. The flurry of white shirts all moving towards the front post drags Villa shirts toward them, enabling Vestergaard to remain isolated at the back post.

A similar story transpires in the away fixture to Man City, with Vestergaard’s header possessing hallmarks that are somewhere in-between the incidents at Brighton and Villa. Again, three Saints shirts drag City players to the front post, leaving Vestergaard room to attack the ball. Che Adams stays at the back post to occupy Kyle Walker.

Hasenhuttl’s approach to particular facets of football demonstrates the game’s evolution. Regardless of league standing, teams have now acquired a courage and a freedom to find innovative ways of working.

It doesn’t have to conform to convention or embrace the same archaic transcripts of bygone eras. Hasenhuttl’s distinctive plans on defensive set-pieces continue to defy traditional viewpoints.

If the offside trap works and the defensive line stays firm, a potential threatening free-kick immediately becomes futile. But if one player steps out of flawless synchronisation, then an opposition forward is left with a chasm of space to finish past a despairing goalkeeper.

The Ralph Hasenhuttl guide to set pieces is one of the first prototypes to be made. While onlookers can harbour severe reservations, evidence suggests there is very little in the way of errors, so far.

Follow us on Twitter @ProstInt

![Prost International [PINT]](https://prostinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/PINTtFontLogoRoboto1536x78.jpg)