Look above. I am the second one along. There are five other players encompassing me, with five coaches towering above me. I am 15-years-old and on a week-long tour of Limburg, Belgium. I am about to embark on my eighth season with the club.

5.12.2016. Almost four years to the day.

I must confess to not be the greatest with dates and marking points in time. I’m hopeless at remembering various anniversaries and close friends birthdays. That, along with understanding the dialect of time – what the hell does quarter past, quarter to mean? Heck, just say the actual time? – are weak, albeit trivial, blots of the mind.

But yet, I can recall every minute detail which transpired on the 5th of December 2016. There I was, donned in full Bournemouth tracksuit attire, sat across the table from four of my coaches. For an everyday teenager, perhaps the thought of a seating plan that elicited four adults – all of whom are quite literally holding your future in their hands – staring at point-blank range would make for an overwhelming feeling of unease. And they would be correct.

Despite these ‘meetings,’ often referred to as player assessments, taking place on a triannual basis with review forms grading each component of your ability dished out every six weeks, things never got easier. The same pressure, the same feeling of worry and insecurity.

But that boisterously cold Monday evening turned out to be different. Even more acute with fret and emotional turbulence. While I traipsed in expecting a sharp cross-examination of recent failings – things had been getting worse for some time by then – I didn’t expect what they were about to say. Just yet, anyway.

In a matter of sentences, I was told my services would not be needed anymore. As they divulged into various ‘exit strategies’ and ticking the boxes of protocol, a distinct numbness took over. The individual that remained ensconced on a chair as he stared straight through the four men in front of him, wasn’t really there. The lights were on, but no one was at home.

Ready to come onto the pitch at Vitality Stadium at half time in 2010 – was then called Dean Court

I knew it was highly unlikely I would be offered a scholarship and in all fairness, deep down I didn’t really want one. I just followed the blunt narrative that all boys want to become footballers and nothing else. If I thought anything contrasting, something was wrong with me. How could you pass up a contract at a Premier League academy. You’ve fought for eight years to stay afloat and when push comes to shove, you are deciding not to fight at all? So like the good little boy I was, I just abided with the storyline.

Nothing could prepare for the hurried nature of it all. The lack of warning I got upon receiving my release felt like an ambush. There was no way I could have prepared for it, or to have installed defence mechanisms to somehow help contend with it. After all, they were telling me with my teammates, some of my best friends, only a few yards away. They were waiting outside of the room that only seemed to be caving in by the second.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Life in an Academy: A disclaimer

Before we enter the crux of this piece please do not misconstrue it to be an overzealous case of sour grapes or finding excuses. Academy football is cutthroat, and only the true elite even make a professional appearance.

In fact, the statistics say that of the 1.5 million boys who play organised youth football in England, only 0.01 per cent will make a single appearance in the Premier League. Even among those who enter an academy structure at the age of nine (the age I was), it is less than one per cent.

The majority of the other 99 per cent fall by the wayside between the ages of 13 and 16. Even among those who are given a scholarship at 16, the overwhelming majority do not reach the top echelon of the Premier League.

It is a convoluted, heavily assessed process that is simply required to sculpt and harden you to be a professional football player. I wasn’t good enough. I did not have the technical or psychological propensity to reach the summit. I do not blame the club for releasing me when they did.

It’s the how part that still rankles.

________________________________________________________

Life in an academy: The days after

In the end, the decision whether to fight or throw the towel in wasn’t left in my hands. The next day after leaving the club I had spent half my life with, I had mock exams, the final curtain raiser before the real thing. The school knew deeply about my lifestyle, which had grown ever more pertinent in recent years, having missed every Wednesday to play football.

They were accepting of it, because they thought I would play football for a living. Everyone knew me as the football guy, so when I lost that, I lost my identity.

Former Watford, Bolton and England Under-21 international Marvin Sordell experienced a similar feeling of loss during the winding down stages of his career, talking to The Athletic, the retired striker said: “One of the psychologists I spoke to explained to me that a player losing their football career was akin to the traumatic effect of losing a loved one, as it’s like losing a part of them,” Sordell admitted. “There has to be a proper process of moving on from that.”

So, like the good little boy I still was, I trudged into the exam halls, still encountering an unabating numbness from the night before. As the papers were being handed out, my mind refused to concentrate. ‘They are letting you go Jacob. The club I joined when they were struggling to make ends meet in League 2 and the team I trained with five times a week are letting you go.’

I didn’t want to admit to myself that by this point, my confidence was at an all-time low. Things got so bad I used to go to bed on a Saturday praying for a thunderstorm or something even more catastrophic to happen overnight so I didn’t have to play the next day. That isn’t right.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Life in an Academy: One year later

December 5th 2017. The shock refused to dissipate. Indeed, it was only just dawning on me how much of a failure I was. I had let my parents down, the two people who took me 45 minutes down the road five times a week.

People at school and by now college, still continued to rip into me. Reminding me of my one true failure. I laughed it off, that’s all you can do, I suppose.

I didn’t understand why I was so upset. Most of my former teammates didn’t even enjoy playing football way before we reached under-16 level. Just keep alive and swimming on top of the water. Refuse to let the thousands of other boys nipping below the surface a chance. Keep working and hope you’ll eventually enjoy the fruits of your labour.

Three months before I left, my coach at the time began to ostracise the players that were set to become culled.

After one particular training session, I was taking off my GPS tracker and complete the parliamentary procedure of shaking hands with each and every one of the coaches. There were 16 boys in the team, 15 of them got a ‘well done, see you later’ from that coach. The other got “JT” followed with a nod and a simultaneous glaze to the floor.

How hard would it have been to stay those two extra words?

I didn’t get to sleep, paranoid with what the coaches, player’s parents and teammates thought of me. Although I had been there for the longest time and held my own against Europe’s top academies and in playing Japan, some countries, I felt like a fraud. That I fluked my way here; that I was now being exposed.

I had withstood the incremental challenges now being in a Premier League academy had brought and yet I only really felt good enough to play for my school team.

___________________________________________________________________________

October 2015. I woke up at 6am for a 9.30am meet in the county of Avon to play Bristol Rovers. I hated long away games. My legs were sapped of energy and by the time of arrival, I had unyieldingly played the game through my mind so much, I was already shattered.

Though the match against Bristol Rovers sticks in my mind because of what happened after. A coach, who I won’t name – but now plays a prominent role in developing young players at another south coast club – spoke after our 4-0 hammering. “Fuck me lads, that was shit. You all need to realise we are not here to have fun and mess around. You’re getting to the age now where you won’t enjoy football, it’s a job.”

I could not believe it. I was 14 at the time. What is the point of playing football if you cannot enjoy it?

From that day forward, all love of playing left me. Intermittently, I would enjoy some training sessions. But playing a game with everyone watching, waiting for a mistake and in my own mind, baying for blood – I couldn’t have thought of a worse place to be.

The next day after Bristol I was back in training. At least half a dozen sets of coaching eyes watching, muttering and murmuring words. By the time I had reached under-16, the make or break age group, my personal level of paranoia was at its most heightened stage. Every pass I made, every decision I took, I would look over to the coaches to seek instant gratification.

With scholarship handouts looming, tension was becoming rife amongst the team. Some boys that I would have sleepovers with, travel to different countries, see more times than members of family, were beginning to exploit any hints of fragility. They would shift blame, suck-up to coaches, and offer an incessant reminder of mistakes in games. They had become a poorly-crafted caricature of themselves.

With me it was worse than most. I have a genetic tremor disorder, where my hands proceed to shake no matter where I am, at any time. The boys had long known this but only when we reached under-16 level, would they bring up the condition. “Stop shitting yourself, JT” was the four words I received every time I touched the ball.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Life in an Academy: Jeremy Wisten

Jeremy Wisten is a few age groups below myself. His dreaded moment came in late 2018, shortly after he turned 16. It was at a near-on identical point of his life as it was mine.

Manchester City, like Bournemouth, offered Wisten a deal to remain part of the academy until the end of that season. Like others, he was informed early in hope that it would give him the ample opportunity to try to find another club. Trials were arranged.

I had something similar lined up, too. I attended what, in somewhat unsugarcoated terms, was a training day labelled an ‘exit trial’. While Wisten was struggling with a knee injury and felt unable to do himself justice, I grappled with a warped combination of paranoia and anxiety.

I attended the trial in the outskirts of London with my friend from Bournemouth, who had suffered humiliation months before I was released, where bullying got so bad during a fitness camp in Marlborough, he withdrew before the season had begun. He didn’t share the intensity or passion for football that I possessed so his departure didn’t quite hit him as hard.

With confidence verging on the cantankerous, I wished the football didn’t come near me that day. Even waiting in the changing rooms with 60 other boys who had been gone through a similar situation at other clubs, paved for an eerie atmosphere. I smelt failure, each player racked with fear but some had more machismo than others so were sufficiently able to cover it up.

Both I, my friend and Wisten’s summers came and went without getting signed up.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Life in an academy: Two years later

It took me two years to comprehend and accept that I had failed and to realise how bad it got. I never thought as myself as depressed and still do not prescribe to that notion, but some resembling signs were there. I would wake up in the middle of the night, running through all the times I touched the ball in training hours before, or analysing every specific word a coach said.

Footballers have historically been typecast as intellectually challenged people. While I can tell you that is certainly not the case, perhaps being that way proves conducive within a ruthless academy set-up. Far from saying I am the brains of Britain – definitely not – I was one of the higher achieving academics in the team and would always go through a series of thoughts, consequences and overthinking before, during and after games.

Players who don’t really think much and just play on instinct are those of whom I envy.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Life in an Academy: Today

Sam Surridge pulling Bournemouth’s second back against Preston – Photo: AFC Bournemouth

On Tuesday, I attended Bournemouth’s 3-2 defeat to Preston North End. It was my 10th visit back to the Vitality Stadium since my release. Every time had been for journalistic purposes.

No fans in the ground and a winterly bitter night that was perhaps fitting for a sense of pathetic fallacy, may have been the perfect pairing for any lingering insecurities to flare up. After all, the place that remained silent and dark throughout had become the sanctuary to my biggest failure in life. Especially when I was situated 10 rows above where I once ball-boyed.

But there was no residue of emotion left in me. If anything, there was happiness in the 86th minute, when Bournemouth grabbed their second. I watched two academy products in Jaidon Anthony and Sam Surridge, both of whom had walked a similar path to myself, combine to get the Cherries back in it.

I can safely say I wouldn’t wish for things to have turned out different. Though I’m sure many will balk at the suggestion, I genuinely prefer watching games from the press box than being on the pitch.

I am one of the lucky ones. I channelled my passion for football into journalism. Others, like Jeremy Wisten, aren’t always given a plan B, or have something to fuel their intense, profound love for the game.

While the 18-year-old was trending on Twitter in the days following his suicide, he soon became just another statistic.

We all say at the time, change has to happen, but who has the unrelenting willingness to ensure it does, long after a traumatic event takes place?

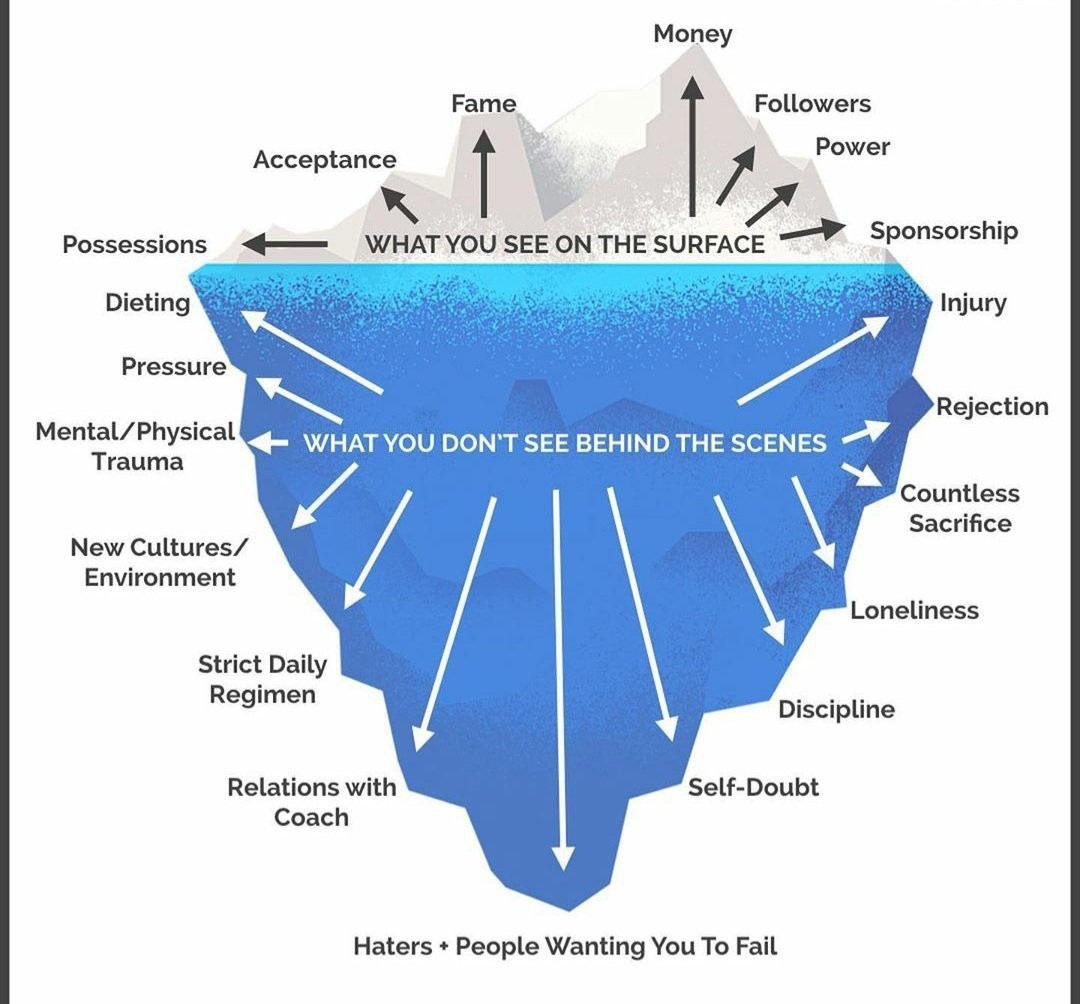

Photo: The psychological iceberg of a footballer – The Athletic

Life in an Academy: Tomorrow

More needs to be done to help those who have suffered the effects of being in an elite footballing environment. Like earthquakes, the aftershock is often more volatile than the initial tremor. Take Josh Lyons, who spiralled into depression after being released by Tottenham Hotspur as a 16-year-old. He took his life 10 years later.

The FA will tick all the boxes and dot the I’s and cross the T’s with how they treat players in the weeks following a releasing of contract. Perhaps looking at the various self-conflicting interests of how they treat those young boys whilst within an academy set-up, is a better place to start.

Earlier this year, a survey by the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) revealed that 22 per cent of current or former players felt depressed or had considered self-harm. Just under 68 per cent said they required support around education, general health general and future career guidance.

55 per cent of players released by professional clubs have experienced clinical levels of psychological distress. The most significant conclusion was that symptoms of distress often increased in the weeks and months after release.

More has to be done.

There is always someone you can talk to. You can call the Samaritans in the UK free any time, from any phone, on 116 123.

Follow us on Twitter @ProstInt

![Prost International [PINT]](https://prostinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/PINTtFontLogoRoboto1536x78.jpg)